Within twenty-four hours this past August on Vancouver Island, two young hockey players died in car crashes. Orca Wiesblatt, a twenty-five-year-old player from the ECHL, was killed in a single-vehicle crash in Nanaimo.

Just hours later, Xavier Rasul-Jankovics, a twelve-year-old who played for the Kerry Park Hockey Association, was killed by a speeding driver, while inline skating with his family in Cobble Hill.

These young people joined a long list of players who have been the victims of road violence. With the puck set to drop on a new season, it’s a good time to reflect on what can be done to prevent more young people dying like this. In short, it’s time for the world of hockey, including Hockey Canada, the NHL, and other organizations linked to our national sport, to rethink its relationship to the automobile, to dream big, and to embrace Vision Zero—a strategy aimed at eliminating all traffic deaths and serious injuries from our roads and at creating safe and healthy mobility for all.

The history

The links between hockey and road violence are long and extensive.

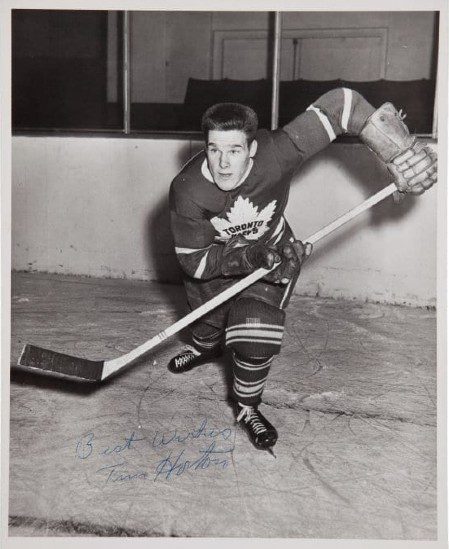

There’s nothing quite so Canadian as popping by Timmy’s on the way to the local rink or after the game, with the team, for a hot chocolate and Timbits. Most Canadians know that Horton was a hockey player. In fact, he was a four-time Stanley Cup champion and, some say, the greatest defenceman in the history of the Toronto Maple Leafs. Fewer perhaps know that Horton died in a car crash. Fewer still know that he was speeding in his Pantera while drunk and high on prescription drugs, a fact that was covered up at the time of his death.

Horton is just one in a series of NHLers who have died in crashes. This list includes, among others, Dan Snyder, Pelle Lindbergh, Luc Bourdon, and Johnny Gaudreau. Gaudreau and his brother Mathew, also a hockey player, were run over while bicycling by the side of a New Jersey highway in August of 2024. His story is particularly heartbreaking: he left behind a young child and a wife pregnant with a second, Carter, who was born seven months after the crash.

Several days after Gaudreau was also killed, another former NHL player, Stephen Peat, also died—the result of injuries sustained when he was hit while crossing the street in Langley, B.C.

A number of prominent NHLers, including Dany Heatley and Craig McTavish, have killed others in crashes, while countless more have sustained life-altering injuries. Perhaps the most famous of these is all-star Detroit Red Wings defender Vladimir Konstantinov. In 1997, just six days after winning the Stanley Cup, Konstantinov was involved in a crash that left him brain-damaged and paralyzed.

The tragedies extend to the junior ranks, needless to say. Arguably the most poignant and horrific crash of the 21st century in Canada involved the Humboldt Broncos junior hockey team. On April 6th 2018 on a Saskatchewan highway, sixteen people died, including ten players between the ages of fifteen and twenty-one.

This crash produced a nationwide outpouring of grief in Canada and attracted global attention, with condolences offered by everybody from Donald Trump to Pope Francis. The crash, incidentally, was a grim echo of one involving the Swift Current Broncos in 1986, in which four young players died.

Why?

These hockey-related crashes occurred in a variety of places and for a variety of reasons. All were tragic for everybody involved. As is the case with nearly all such crashes, however, they were described in the media and elsewhere as products of poor individual choices and/or as “accidents,” that is to say, as quasi-mysterious acts of fate. Of course, some of these crashes did involve reckless behaviour—nobody would deny that. But drunk driving and speeding are in part the products of lax law enforcement. People do these things because they think they will get away with it. Not enough emphasis has been placed on the social conditions and public policies that allow such vehicular tragedies to occur.

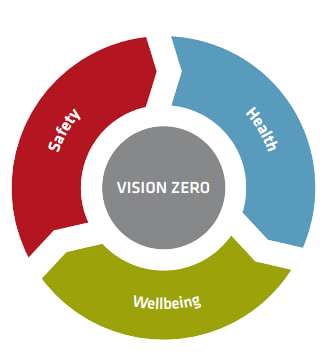

And that’s where Vision Zero comes into the picture.

Vision Zero is a strategy for eliminating road violence and for creating safe and healthy mobility for all. It puts the onus on government to provide us with safe streets. Many dismiss Vision Zero’s dream of a world without traffic fatalities as a well-meaning fantasy. They argue that fatalities and injuries are the price we pay for the freedom and convenience provided by automobiles. (When they say this, they assume, of course, that they or their loved ones won’t be among those injured and killed.) Or, more fatalistically, they shrug and say “shit happens,” and there isn’t much you can do about it.

But significant change is possible. To see that, we only need to look at the history of another hockey powerhouse—Sweden. In 1997, Sweden became the first country to officially adopt Vision Zero policies. Since then, the number of deaths and injuries on its streets has been halved. In 2002, neighbouring Norway followed Sweden in adopting Vision Zero principles, and its roads are now the safest in Europe.

| Country | Deaths per 100k (2021) |

| Canada | 4.7 |

| Sweden | 2.1 |

| Norway | 1.5 |

Let’s look at the numbers. In 2021, in Canada, 4.7 people died in car crashes per 100 000 residents. In Sweden, 2.1 people died; in Norway, only 1.5 people did. To put that in absolute terms, in Norway, 82 people died in crashes; in Sweden, 210 died, and in Canada over 1,800 died. (In the United States, meanwhile, a staggering 47,000 died in that year alone, 14.2 per 100 000.)

Another way of thinking about this is that a child in Canada is over three times more likely to die in a crash as they are in Norway.

It doesn’t have to be this way, and with the right policies it won’t be.

The solution

The hockey community should urge governments to adopt policies that will save lives.

An important petition is currently circulating in support of Xavier’s Law, which would toughen B.C.’s dangerous driving laws.

Much more can be done. Hockey has made billions from big automobile companies.

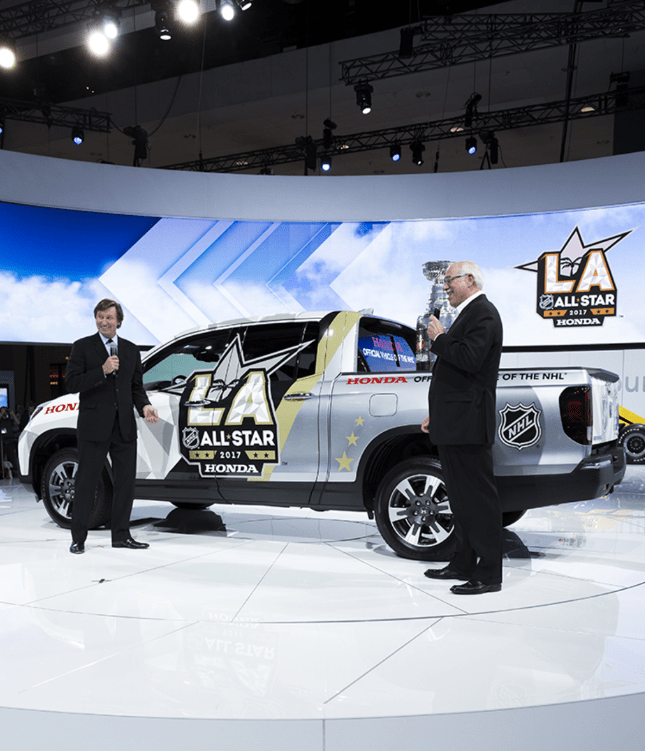

During the commercial breaks of any NHL game, the audience is subjected to a stream of advertisements for trucks and SUVs, which seem to get bigger with each passing year—all these ads, subtly and not subtly, glorify speed and power. Over the years, many players have had lucrative deals endorsing car companies. Long before he was shilling for the online gambling industry and donning a MAGA hat, for instance, Wayne Gretzky was a spokesperson for Nissan. The NHL itself even has two “official” car brands: in the US, it’s Honda, and in Canada, it’s Hyundai.

It’s time, however, for the world of hockey to rethink its relationship to the automobile and to take traffic safety issues much more seriously. Young people like Orca Wiesblatt and Xavier Rasul-Jankovics do not need to die.

It’s time for the world of hockey to embrace and endorse Vision Zero.